Bob Nolan biography

1935–1940

Community Sing promotional picture, 1939

(Courtesy of Jan Scott collection)

Bob’s Life

Introduction - The Myth and the Man

1908 - 1931

1931 - 1935

1935 - 1940

1940 - 1941

1941 - 1942

1942 - 1943

1944 - 1946

1946 - 1949

1950 - 1980

Bob’s Family

Harry Nolan (father)

Flora Nobles Hayes (mother)

Earl Nolan (brother)

Mike Nolan (half-brother)

Mary Nolan Petty (half-sister)

Roberta Nolan Mileusnich (daughter)

Calin Coburn (grandson)

Bob Nolan was heavily involved in the beginning of the “singing cowboy” movie craze. His song “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” lent its name to Gene Autry's first feature-length starring film and was Republic Pictures' first step into the western genre. Another of his songs, “Moonlight on the Prairie,” was used as the title of a movie starring Dick Foran. (The Sons of the Pioneers did not appear in either of these.) Those two movies laid the groundwork for the singing cowboy B-western, which remained popular for 20 years. Bob eventually appeared personally in and wrote songs for at least 88 films from 1935 to 1948.

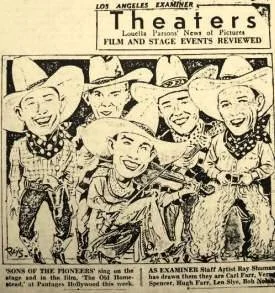

As their popularity grew, the Sons of the Pioneers almost immediately began appearing in movies—first in shorts and then in feature-length movies—but always as musicians. Radio Station KFWB was affiliated with Warner Brothers Pictures, which used the Sons of the Pioneers’ voices in animated cartoons such as A Feud There Was and featured them in some of El Brendel’s comedy shorts, including Radio Scout, released by First National in 1935. Before the end of the year they had appeared in seven more films and shorts. In August 1935 Universal released the Oswald the Rabbit cartoon Bronco Buster, which featured music by the Sons of the Pioneers, including a revised version of Bob Nolan’s song “Hold That Critter Down.” They signed with Columbia Pictures to provide music for the Charles Starrett western action series and remained with them until 1941.

THE FIRST MOVIES

The Sons of the Pioneers began their own movie career with the Liberty picture The Old Homestead in 1935, but the year before that, Nolan’s voice made its film debut in Mascot's In Old Santa Fe, starring Ken Maynard. Maynard was a handsome, reckless, popular western star who liked to sing, but the studio was unsure how the public would accept his high, thin vocal effort. So they recorded Nolan singing “That's Why I Like My Dog,” and Maynard mimed it in the first scene.

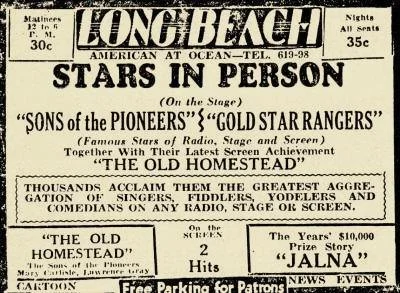

The Pioneers’ feature film debut as The Gold Star Rangers was not in a western but in the role of farm boys who hit it big on radio in Liberty Pictures' The Old Homestead, starring Mary Carlisle. They performed “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” “There’s a Roundup in the Sky,” “Happy Cowboy,” and “This Old White Mule of Mine,” all songs by Nolan.

(Courtesy of an anonymous collector)

In September 1935 the Pioneers appeared in the short films Radio Scout (Warner Bros.), Bronco Buster (Universal), then Hal Roach's Slightly Static, starring Thelma Todd and Patsy Kelly.

A production still from the short Slightly Static (1935 09 07), courtesy of Ed Phillips Back: Karl and Hugh Farr, Tim Spencer, Leonard Slye and Bob Nolan.

Front: The Randall Sisters.

"My grandmother, Ruth, is in the middle in the photo. On the left is her older sister Shirley and on the right is her older sister Bonnie. I am contacting a man who owns many of the old radio shows called Pinto Pete & the Ranch Hands. Apparently the Sisters (first called Aaron Sisters, their actual last name, then the Randall Sisters) sang is dozens of these shows."

(Jennifer Putnam)

Mack Sennett, of Keystone Kops silent film fame, released the short Way Up Thar, starring Joan Davis and featuring the Sons of the Pioneers singing Nolan's "Barnyard Jubilee." Add Romance of the West (Warner Bros.). They also appeared in the two B-western feature films for Columbia (Gallant Defender and Mysterious Avenger). Nolan was seen and heard on screen by 1935. Audiences who craved music with their action. Sound in movies was less than 10 years old, singing westerns were popular, and the Sons of the Pioneers were a good-looking group of men who sang beautifully.

Way Up Thar

(Karl E. Farr Collection)

The Sons of the Pioneers wrote the songs and appeared with Charles Starrett in Columbia's Gallant Defender, the first of thirty films with the cowboy star who became "The Durango Kid". The Pioneers had no real acting parts; just song sequences around campfires plus work as extras.

These were busy days. They were singing on Dr. Cowan's (dentist) radio program early in the mornings and then going over to the Columbia lot by 6:00am to get ready for the day's shooting which began about 7:00am. Gallant Defender cost roughly $150,000 to produce and took about three weeks to complete. Finding titles for all these B-Westerns was a challenge and the way Columbia handled it was to get all the office staff together - stenographers, secretaries, etc - and show the new film to them. They would all submit a name and whoever won would get the $15 prize.

Sound in the movies was in its infancy and the people wanted music as well as action. These were heady days for the young men. They did not make much money from the films or from the Standard Radio Transcriptions and they had to work extremely hard but they were becoming familiar to movie and radio audiences across the nation - audiences who would buy their Decca records.

Douglas B. Green explains the reason for their quick rise to fame:

"Their songs were sweeping and majestic. They were about the west. They were about the wide-open spaces and the free life and fresh air; not so much about branding and taming wild horses. They took those old songs of the trail and the endless ballads in three chords and completely revitalized them with their musicianship and their songwriting and harmony. Nobody was singing three part harmony, yodeling in harmony, like that. It was unheard of when they started in the 30s."

If 1935 was busy, 1936 was hectic. And exhilarating. The group continued their radio broadcasts on KFWB, made an appearance with Bing Crosby in Paramount's Rhythm on the Range and supported Dick Foran in two Warner Brothers films. Roy's personal life was chaotic but settling down. On June 8, Roy received his divorce from his first wife, Lucille. On June 11, he married Arline Wilkins in her hometown of Roswell, New Mexico. From there, the Sons of the Pioneers and Roy's new wife traveled to the Texas Centennial at the Dallas fairgrounds where they performed from six to eight (some sources say three) weeks at the Texas Centennial in Dallas. The group appeared in two Gene Autry Republic films and another Charles Starrett picture for Columbia. Cross and Winge of San Francisco published two of the three Sons of the Pioneers' song folios. All during that time they were constantly expanding their repertoire. Somehow they fitted in recording sessions with Decca and recorded fifty-six sides.

Because they were on staff at KFWB, they might have two or three programs a day and they needed new songs constantly. They also appeared on KFOX in Long Beach, KRLD in Los Angeles and as The Gold Star Rangers on both KFWB and KMTR in Hollywood. They depended heavily on old-time songs but Bob and Tim were continually writing new ones, too. This is how Bob described it:

“We wasn’t going to do anything that anybody else did at all. We had to do a lot of "Gay 90’s" stuff like "Annie Rooney" because there was an insatiable demand at that time for harmony singing. And we were on radio at least an hour a day, every day of the year, and sometimes two hours.

We had to have an awful lot of material, and that’s where we beat everybody else to the top spot because we had a repertoire at the time (after we had taken the job at KFWB) of at least three thousand songs, all committed to memory, both words and harmony. No other group in town could match us.

I would take the lower register and Roy would take the lead, and Tim would take the top. Sometimes we were infringing on each other; like the tenor would be the high baritone and I would come up into the low tenor. We just felt the thing as we went along. It was a wonderful group to work with when it was young, when we were all working on it real hard.”

In 1935, the Sons of the Pioneers made a guest appearance in Gallant Defender with Joan Perry (above) and Charles Starrett.

June 28, 1935

(Photo courtesy of Laurence Zwisohn)

“The phone in our boarding house was ringing morning and night. All the popular radio shows of the day wanted us to perform, and to top it off we even got invited to a benefit for the Salvation Army in San Bernardino. That came about because Will Rogers had personally requested that we appear!

Will Rogers was my hero. He went through hardships and came out with his wit intact. He looked at America from the poor man’s side of things, not from the point of view of the rich bankers and powerful politicians who usually get their thoughts heard.

After the show Will Rogers visited with the band awhile and shook our hands one last time, telling us that he and his airplane pilot Wiley Post had to get going because the next day they were heading off for Alaska. That night would be the last time anyone saw Will Rogers on stage. His plane crashed on that trip [August 15, 1935], killing all aboard.”

(Roy Rogers, pp. 65-66 , Happy Trails: Our Life Story, by Roy and Dale with Jane and Michael Stern, Simon & Schuster, 1994) [Note discrepancy in dates.]

Will Rogers, with his homespun wit and wisdom, was well-known to most Americans in the 1930s. He was admired as a man who could talk about the ills of life and politics in a humorous way. The whole country mourned his death and Bob wrote To Will Rogers as a tribute. The melody has been lost or forgotten now.

Tim Spencer’s song, "Will Rogers’ Last Flight", is in The "Sons of the Pioneers Song Folio No. 1", 1936, Cross & Winge. "To Will Rogers" was registered for copyright in 2004 by Bob Nolan's grandson.

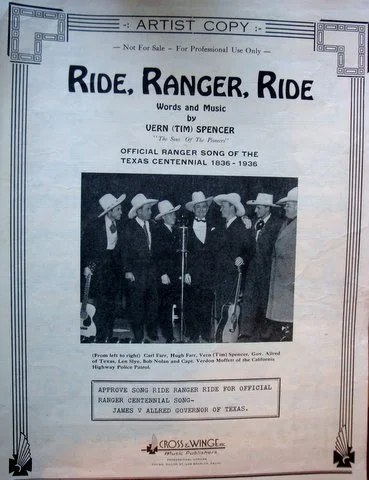

THE TEXAS CENTENNIAL

At the invitation of Texas Governor James V Allred, the Sons of the Pioneers made their first public appearance outside of California at the Texas Centennial Exposition. Dale Evans remembers seeing the Sons of the Pioneers there: "I was walking through the Centennial there at Dallas and here was this huge exhibit by Gulf Oil and a bunch of boys standing behind a glass performing, just almost non-stop."

(Courtesy of the Karl E. Farr collection)

(Courtesy of John Fullerton)

(Courtesy of the Roy Rogers Family Trust)

1936 The Sons of the Pioneers at the Texas Centennial with, possibly, Leo Spencer.

(Courtesy of Laurence Zwisohn)

Cover of Tim Spencer’s “Ride Ranger, Ride”

(Courtesy of Karl E. Farr collection)

Cover of Tim Spencer’s “Ride Ranger, Ride”

(Courtesy of Karl E. Farr collection)

Closer view of above. Caption text reads:

(From left to right: Carl [sic] Farr, Hugh Farr, Vern (Tim) Spencer, Gov. Allred of Texas, Len Slye, Bob Nolan and Capt. Verdon Moffett of the California Highway Police Patrol.

(Private Collection)

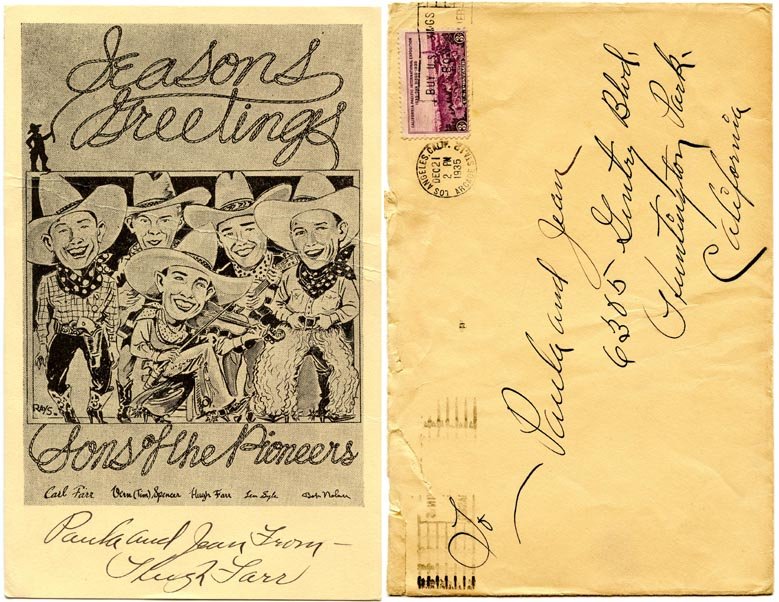

Postcard from Hugh Farr to a Fan

(Courtesy of an anonymous collector)

Scene from The Big Show they were currently appearing in with Gene Autry that was filmed on the Exposition site.

At the site they had their first taste of rubbing shoulders with the federal government when they had their photograph taken with Vice President Garner. They also recorded two sides for Decca while they were in Dallas.

Newspaper clipping from the Hollywood Citizen-News, 1936. Left to right: Bob Nolan, Hugh Farr, Tim Spencer.

Caption reads: “’CACTUS JACK’ AND COWBOY CROONERS – Vice-President Garner flatly refused to pose for ‘gag’ pictures at the Texas Centennial Exposition. Rangerettes, fishing in the world’s fair lagoon, and a dozen other stunts were spurned but – well, cowboys are different and so he put on his ten-gallon hat for the photographer.”

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

Amon G Carter (creator and publisher of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram) and unidentified man with the Sons of the Pioneers

(Courtesy of a private collecer)

With Bing Crosby and Leo Spencer in Rhythm on the Range publicity still, 1936, at the Texas Centennial.

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

Text from the back of the photo

Shortly after the Sons of the Pioneers returned from the Texas Centennial, Tim Spencer left the group in sympathy with his brother, Leo, who had been released from his managerial chores; Tim did not return until early in 1939. They were still singing on radio both as The Sons of the Pioneers and Farley's Gold Star Rangers. Wesley Tuttle and Charlie Quirk took Tim's place for a few weeks and then nineteen-year-old Lloyd Perryman with his beautiful lyrical voice was hired.

When Tim left the Pioneers it must have seemed that it would be the end of the group. They had to find someone quickly to take his place. During this time, Lloyd was substituting for members of the Sons of the Pioneers when they had to be out of the group and coincidentally he joined Jimmy LeFevre and His Saddle Pals. Roughly nine months after Tim’s resignation in September, 1936, Bob Nolan called Lloyd up and asked him if he would like to fill the spot left by Tim. Lloyd jumped at the chance and never looked back. He was 19 years old.

The sound of the trio had been built around Nolan’s distinctive bubbling baritone. They experimented by having each man move from position to position in front of the mike. After Perryman joined, the trio harmony became more exacting and Nolan noticed that when he was in the middle he found Spencer and Perryman listening to his voice and he could more easily hear theirs. Bob remembered the smiles as they acknowledged their approval of the new arrangement. Nolan’s voice overlapped and locked in all three voices. With the addition of Lloyd Perryman came a subtle change in style as he gradually took over the arranging. By the late '30s, the inimitable Sons of the Pioneers' sound was in place. Few have been able to duplicate it.

Bob thought the world of Lloyd. Both families were close. Even after both men were gone, their wives, Buddie and P-Nuts, remained best friends until they, too, died. Bob said there was no one like Lloyd to interpret the feeling and spirit of his songs. In fact, only Lloyd could sing Bob's difficult compositions as they were meant to be sung. His voice was as integral to the sound of the Sons of the Pioneers as Bob's, or Hugh's fiddle, or Karl's guitar.

“It's pretty obvious the Pioneer blend improved after Lloyd joined the group. That wasn't only because of the quality of his voice. It had a lot to do with the way they stacked their voices.

What I hear in the stacking of voices after Lloyd joined was a definite attempt to keep the harmony parts in a comfortable range for each one of the singers so that no member was straining to reach a note, whether it be a high or low one. That is what contributes most to the quality of blend associated with vocal groups...keeping everyone singing in a comfortable range.

Most melodies stay within a certain range whereby the middle voice can handle the whole thing with no difficulty. In that case, the tenor sings a regular tenor part usually three notes above and the baritone fills in the remaining note of the chord below the melody (i.e. "When Payday Rolls Around".). However, some melodies may traverse a full octave range or more during the course of a song. When that happens, its best to assign parts of the melody to individual ranges.

That's why they often distributed different parts of the melody line to different members of the trio as they proceeded through a song. Once the decision was made to stack voices so that everybody was singing in a comfortable range, that procedure was applied to all songs, regardless. The stacking, of course, was the baritone on the bottom, the tenor on the top, and the third voice in the middle. Whether Lloyd was responsible for that, I don't know. I do know that he was definitely responsible for the interpretation and vocal stylings of most of the songs the Pioneers did down through the years.

Tumbling Tumbleweeds is a classic example of this procedure. With the voices always stacked the same (baritone on the bottom, then the middle voice, and finally the tenor on top), the first two lines of the song begin with the melody in the tenor or top part. In the third line the melody is carried by the middle voice, and in the fourth line ("Drifting along with the Tumbling Tumbleweeds") the baritone or bottom part carries the melody. The voices remained stacked the same regardless of who is carrying the melody. This is repeated throughout the song. Most all the top Western vocal groups have followed this same procedure down through the years.

The main goal was to have every member of the trio comfortable with the range he was singing in. The logical result was to have Bob Nolan on the bottom, Tim Spencer in the middle, and Lloyd on top. This arrangement never varied. From that point, it was just a matter of picking a comfortable key for all three to sing in depending on what the melody did in any particular song.

Also, remember the blend prior to Lloyd was a little more strained because Tim Spencer was handling the tenor chores above Leonard Slye and often singing at the top of his range. When Lloyd became part of the trio, Tim dropped down to the middle range and the sound became much more relaxed and smooth. Also, Lloyd added an exceptional tenor voice to the blend, much better suited for that part than Tim's.

Dick Goodman of The Reinsmen

Bob Nolan's autograph refers to a popular song at the time, "Stay as Sweet as You Are" (Mack Gordon / Harry Revel) from the film College Rhythm, 1934

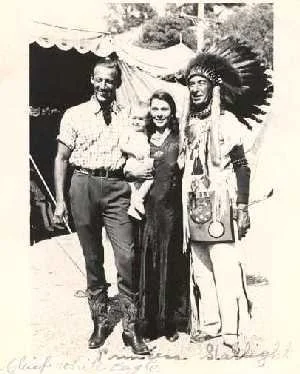

In 1936 with Chief White Eagle and Princess Starlight with their baby, Ne Ha Nee, for whom Bob wrote one of his songs.

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

In 1937, Leonard Slye became "Roy Rogers", but not right away. Because of contractual problems with Gene Autry, Republic Pictures hired Roy on October 13 and started grooming him as a replacement for the popular singing cowboy. He was given a new name, Dick Weston, and Pat Brady took his place with the Sons of the Pioneers. Roy finished recording as a member of the Sons of the Pioneers on December 16 when they cut their last side for ARC (Columbia Records). They also recorded on such labels as Banner, Romeo, Melotone, and Perfect for “Uncle” Art Satherly.

Bob told Bill Bowen that a lecture from Ernest Hemingway in 1937 was one of the greatest things that had ever happened to him. Hemingway had just returned from the war in Spain and was much sought after. Robert Ruark, a writer friend of Bob's, persuaded him to attend a six-hour seminar given by Hemingway at UCLA. Ruark was a protégé of Hemingway’s and knew that Bob, a lyricist, would learn much from him. The lecture was to be limited to forty writers under thirty years of age and cost $50. Bob said this amount was a fortune to him in 1937, but he took some savings out of the bank and borrowed the rest.

“I would have stolen to get that $50 to spend that time with Ernest Hemingway. We went in at 3:30 in the afternoon and left after 9:00. We had two meals with him…and he was one of the most gracious persons I ever met. He treated us like his children and the things he taught us that afternoon I will remember for the rest of my life. He taught us what it was to write and make our writing readable…re-editing until you got the words to mean exactly what you wanted them to mean. I’ve always had that in the back of my mind. I would write a song and go home and live with it and re-edit it and re-edit it until the words became a—what did he call it?—a sword, not a word—a cutting sword. That’s the key to the whole thing—the proper word. Re-edit and re-edit until the proper words are in their proper place. Understand you didn’t have to go to the dictionary. One thing I never did was make my listener go to the dictionary to find out what I was writing about. I spoke his language.”

(Note: Editions of Hear My Song through 2004 stated that the price was $500. Bob told Laurence Zwisohn it was $50, not $500, and Robert Ruark’s biographer agrees that it would not have been $500. The upcoming edition of Hear My Song will correct the error.)

THE OPEN SPACES PILOT

1937 saw the Pioneers moving to KHJ where they had a spot on Peter Potter's Hollywood Barn Dance with the Four Squires and the Stafford Sisters—Christine, Pauline and Jo, etc. The voices of the Sons of the Pioneers and the Stafford Sisters blended beautifully and Bob conceived the idea of joining the two groups and calling themselves The Sons and Daughters of the Pioneers. He put together a pilot radio show, The Open Spaces, with Harry Hall as MC. It was aired at least once and then dropped. Jo Stafford remembers the fun they had together building the program and even now she cannot understand why it did not catch on.

"The commercial (term for a radio pilot for a series) was recorded while the Sons and the Staffords were on the Hollywood Barn Dance radio series. As best I can tell the Pioneers first appeared on the Hollywood Barn Dance in September 1937 and continued thru April 1938. So successful was their work on that series that Roy alone was invited back for a guest appearance in December 1945. So sometime between September and April was when it would have been recorded."

(Laurence Zwisohn)

The Pioneers and the Stafford Sisters were friends off-stage, as well, and Bob and Christine saw a lot of each other. In fact, one night on a beach in Oregon with Christine Stafford Bob composed his famous song, Wind.

Christine and Pauline Stafford

Wally Smith clearly recalled listening to the Sons of the Pioneers when they were first on Hollywood Barn Dance. He noticed that Bob avoided saying too much about his younger days because he had trouble choking back tears when he did, something he did not want to do on air.

Wesley Tuttle agreed that Bob was very sentimental. He also remembered going to Bob Nolan's apartment to record a song, Juanita, for Wesley's mother. Bob had a new home recorder and the records were heavy paper with a chemical coating that deteriorated each time it was played. Bob was intrigued and delighted with his machine and used it a lot. Of course, the "records" he made are long since gone. Bob, Wesley said, couldn't read a note in the early days and didn't know the names of the chords he played. He also used a capo if he wanted to change out of the key of C.

“I chose western music as a career from listening to the North Texas stations in the mid-30s and it wasn't long before I began to hear the great transcriptions of the Sons of the Pioneers. We were so impressed with the Pioneer harmony that our first trio of Jimmy Wakely, Scotty Harrel and myself patterned ourselves after them. I sang "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" when I auditioned for my first radio job.”

(Johnny Bond)

COLUMBIA PICTURES

(For a complete listing of all the films that included the Sons of the Pioneers, see The Movies)

When the Roy Rogers and Dale Evans Museum was in Apple Valley, California, Laurence Zwisohn copied the particulars of the contract between Columbia and the Sons of the Pioneers dated August 1, 1937. "[They were] paid $8,000.00 for eight films. Two weeks later they began working on Old Wyoming Trail. The next film didn't begin until October 22 by which time Len had been signed by Republic."

They now had supporting parts as a group of cowhands, etc, and provided at least two and often four songs for each film. When Tim left the group in 1936, the entire songwriting load for each film fell on Bob's shoulders for well over a year. He composed new songs and selected some of his old poetry to put to music. "There wasn't a day," he said, "that I wasn't working on at least two songs at one time."

When Roy left for Republic on October 13, 1937, he had to resign from the Sons of the Pioneers who had been newly signed by Columbia Pictures. The contract specified a certain number of members of the group but not which ones, so Len suggested his friend, Bob O'Brady, as his replacement. Because there was already one "Bob" in the group, O'Brady changed his name to "Pat Brady". Pat took Roy's place as "toby" or comic, a part to which he was perfectly suited. Pat was a good bass player but, on his own admission, he didn't take life seriously enough to apply himself. He endeared himself to audiences with his Danny Kaye-like appearance and natural humor. He was shy and, like so many shy people, loved to make people laugh. He was as funny off-stage as on.

Children loved him, the Pioneers loved him, but his voice didn’t fit into the trio because he was accustomed to singing comic songs. Tim Spencer was invited back but the Pioneers kept Pat. He arrived in time for Outlaws of the Prairie, in 1937. And so Pat became a "movie star" although the pay was poor - $33 a week. Here's how Bob put it:

“We knew Pat could sing, but he couldn’t harmonize, see. His voice would not---we could not harmonize with him at all. He’d been singing comedy so darn long, see, that he had no way of knowing what we were talking about when we said, "Blend."“

(Bob Nolan, taped interview)I made a working sheet of the lyrics and wrote down what I wanted to say in the song or the picture I wanted to paint. It's just like a libretto with a scenario. I would write a small synopsis of what I wanted to do and go to work from there. If the tune was suggested by the thought, or any of the lyrics written, then I'd go to work on the music. There was no set pattern with the exception of first writing down what I wanted the song to say.”

(Bob Nolan, Hear My Song p. 135 )

Bob was having a different kind of voice trouble. Although his unusual voice was perfectly acceptable to Warner Brothers when it was dubbed in for a villain singing Vengeance in a Dick Foran flick, Song of the Saddle, and it was acceptable to Mascot when it was dubbed in for Ken Maynard, someone on the Columbia staff didn't think it was acceptable for the second lead. Columbia dubbed in a trained baritone for Bob's solo parts for the first year. You can hear one of these dubbed baritones in Bob's song, “Bronco Pal”, from the movie Rio Grande. But, while Bob was miming to the dubbed voices, the Sons of the Pioneers had difficulty restraining their laughter on screen. Bob himself could not resist hamming it up just a little. If the Columbia powers-that-be didn't like his voice, the public did and they demanded it back. They were quite familiar with his voice from his years on radio and loved it. After a few films, Columbia bowed to their requests and Bob sang his own songs from then on.

COSMETIC SURGERY

Bob's character parts improved as the studio recognized his potential. In early 1938, second lead Donald Grayson left the series due to a botched nose job, Bob was moved up into his place. The studio insisted that Bob, too, have his handsome aquiline nose trimmed to "star quality" and in August of 1938 he reluctantly underwent the required cosmetic surgery. "I didn't see anything wrong with my perfectly good Roman nose!" But no one argued with the boss, Columbia's Harry Cohn. He was the king, the star-maker, and a lowly actor did as he was told or he was out. The new nose was nowhere near as handsome as the original but the boss was satisfied and the studio continued to groom Nolan for better parts.

“I felt so bad because I knew Bob before he went and had a nose operation. Bob Nolan was very good looking - romantical and mystical looking. And then he went and got his nose operated on. I don't know why he wanted to do it. After that I saw him in some picture and I couldn't believe. They did, maybe, a real inexpensive plastic surgery job. They took some of the bone, too. Poor Bob. He must have gone into a nightmare when he saw himself. It was like a mutilation. It was very bad! After that, he must have gone to a better plastic surgeon that cost a lot more, maybe, and they fixed the bone. I don't know what they did to the tip but they made it look a lot better. When they fixed it, it wasn't as good as his original nose but it was a lot better. He could get along with that. I always felt bad about that.”

(LaVida Dallugge Brickner, fan)

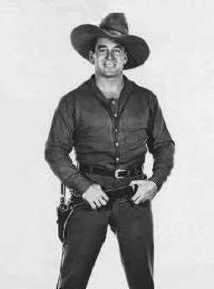

Left: Donald Grayson, 1937 Right: Before and after the cosmetic nose surgery (Digital comparison by Larry Hopper)

The studio had Bob dress like George O'Brien, one the most popular western action stars of the '30s. Older than Nolan by nine years, O'Brien was a natural athlete, a heavyweight boxer and a man with a powerful physique who worked for Fox Studios and then RKO. Bob Nolan, with his lighter but beautifully proportioned frame was Columbia's hope for a "George O'Brien" in their own stable of actors. (O'Brien objected to having singers in his films although some members of the Sons of the Pioneers did appear in some.)

Left and right: Bob Nolan. Center: George O’Brien

In those early years as second lead to Charles Starrett, Bob obviously did his best to improve his acting skills without benefit of formal theatrical lessons, depending instead on the director and the other actors for tips. He was comfortable in his roles as Charles Starrett's right hand man which were better than any role he had in the later Roy Rogers / Republic films. He knew his lines and threw himself into his character roles with an energy that matched Starrett's. Practice perfected a quick draw that would impress any movie gunfighter and no one was checking to see if he could hit a target. In the fight scene in Texas Stagecoach, he gave a believable performance and needed no stunt man to improve on it. One viewer, after watching the scene, observed, "If it had been a real fight, Bob would have won!"

In 1939, while Columbia's Harry Cohn was producing the film, Golden Boy, with William Holden, he was also planning a series built on the story. One day, he watched Bob Nolan crossing the studio yard and thought he had found his man. Here's how Bob tells the story:

“When Harry Cohn (when we were working at Columbia) was going out to lunch and we was just coming back, he stopped his whole entourage and pointed a finger at me and said, "There’s my "Golden Boy!" It scared me, so I went out and got drunk and stayed drunk for a week until he gave up on me! I never wanted that responsibility.”

(Bob Nolan)

While Bob had convinced himself that staying drunk for a week proved to Cohn how "unreliable" he would be for a series of his own, in actual fact he was a very reliable actor. He was the only one of the Sons of the Pioneers who appeared in every film. He enjoyed working in those early movies although he lacked the ambition to be a star. He was content to be a supporting actor because it gave him time to write his music and it freed him from the social obligations that burden a star. Still, the public loved him and he found himself titular leader of the Sons of the Pioneers. He always denied that he was the leader, that there was no leader, but Bob could not deny that he was forced into fronting the group. He had a pleasant speaking voice, a contagious smile and, of a group of handsome men, he was by far the best-looking.

Charles Starrett had nothing but good to say about Bob. He told Mario de Marco

"I enjoyed working with Bob as much as any person I had ever worked with, whether it was theater, radio, television, or anything. Bob was a wonderful person - a strong person and a good musician and a very poetic sort of a person. He saw into people, too. He was a loner."

Harry Cohn

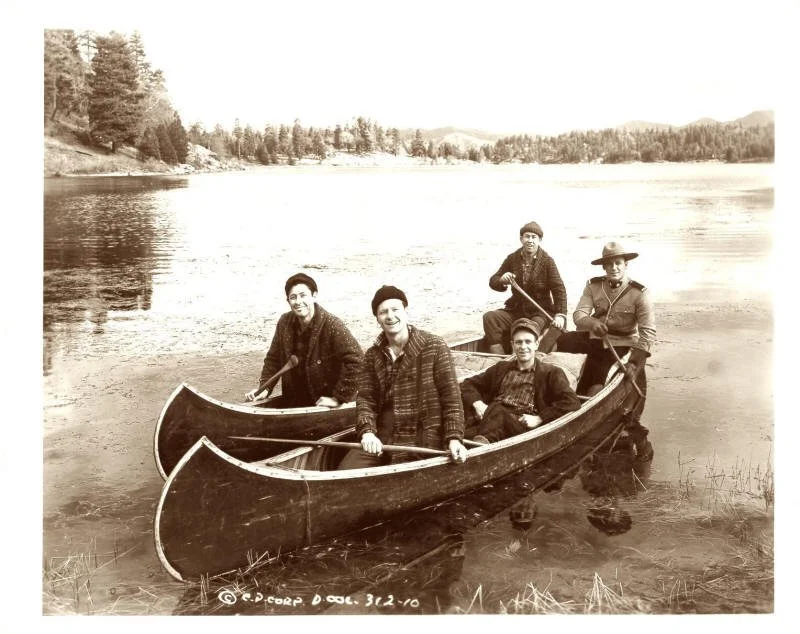

The Sons of the Pioneers with RCMP officer Bob Nolan in North of the Yukon

Ray Whitley took over the management of the group while they were with Columbia. Gerald Vaughn, Ray Whitley's biographer described Ray's involvement in the Pioneers' career:

“Ray met the Pioneers at the Texas Centennial in Dallas in 1936. Ray and his musical group, the Six Bar Cowboys, were featured there for several months extending into the summer and the Pioneers came in from Los Angeles for a special three-week engagement in July-August.

Friendships naturally grew between Ray and the members of the Pioneers, becoming closer when Ray went to Hollywood that summer to appear in his first western movie feature, Hopalong Cassidy Returns, starring William Boyd. Staying in Hollywood, Ray's career and the activity of the Pioneers were sort of parallel at that time. They all were well-known recording artists, all trying to get a break into Western movies, and all doing a lot of radio and personal appearances around Los Angeles. When Ray was a regular on the popular Hollywood Barn Dance radio show, he suggested to its producers that they acquire the services of the Pioneers at the first opportune time. The boys became available and Hollywood Barn Dance grabbed 'em.

In this way the careers of Ray and the Pioneers were touching each other. Also as friends they all were increasingly buddying together. Ray always enjoyed scuffling around and laughs about their pastime of wrestling on the beaches. Ray later managed light heavyweight wrestling champion Red Barry and at a private party in Texas, Ray once wrestled none other than boxing immortal Jack Dempsey. But Ray recalls he never could get a hold on the athletic Bob Nolan.

Ray had been managing the business affairs of his own Six Bar Cowboys for some years and when Tim Spencer left the Pioneers for a year in 1936-1937 ['38 or '39], the boys asked Ray to manage them. Ray's managerial arrangement began around February or March 1937 and continued until he went under contract to RKO movie studio seven or eight months later, about October. As the Pioneers' manager, Ray would book them for engagements. A theater in Covina and a party in Bakersfield specifically come to his mind. He recalls that by 1937 the Pioneers had their arrangements and blend of harmony so perfect that they needed to rehearse very seldom between jobs. Though present at their rehearsals, he offered no suggestions on what they were doing because it was so perfect.

The Pioneers had been recording for Decca since 1934. In addition, Ray approached Uncle Art Satherly suggesting the mutual benefits if the Pioneers recorded for Uncle Art's American Record Company as well. As a result, in October and December 1937, the boys cut a number of great sides for ARC. In 1935 and 1936 the Pioneers had appeared in a couple of western movies starring Charles Starrett at Columbia studio. In 1937 they asked Ray to attempt to negotiate a contract with Harry Cohn, Columbia's chief executive, whereby the Pioneers would become the regular musical group in Starrett's westerns. Cohn was one of the hardest-nosed businessmen in Hollywood. Ray made it clear that if Cohn wanted the best, he wanted the Sons of the Pioneers. The negotiating got pretty hot with Ray trying to get the boys what he knew they were worth. Reaching an impasse, Ray finally agreed to take Cohn's contract offer back to the Pioneers but he told Cohn he wouldn't sign it himself and wouldn't recommend it to the Pioneers. The Pioneers made their decision democratically, took a vote and, despite Ray's reservations, decided to accept the contract.

Although Ray actually felt ashamed of the contract as he felt it was grossly underpaying the Pioneers, he agrees that their acceptance of it was best after all. The movies usually took only one week to film; instead, he got the Pioneers a two-week guarantee on each movie. Each member received about one-half as much as he deserved. The studio demanded first call so Ray got the fellas a bonus to pay for purchasing electrical transcriptions to replace themselves on radio while busy making pictures. In addition, Bob Nolan and Tim Spencer as songwriters were able to supplement their incomes still further by selling songs to the studio for use in the movies. This was on top of earnings from radio, recordings, and personal appearances where the Pioneers continued to be active as before.

The long-term benefits for the Pioneers came through the greater exposure they obtained via the Starrett movies. Starrett moved steadily upward among the top ten western stars, from 9th in 1937 to 4th in 1941 when the Pioneers' last movies with him were released and the boys teamed up again with Roy Rogers. Ray appeared in one film with the Pioneers, The Old Wyoming Trail, before he was contracted to RKO.”

Ray Whitley

The Pioneers sang “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” over the opening and closing credits of each film (except North of the Yukon) and each member was paid a small weekly salary. Bob received very little money for the use of his songs and Tim reportedly sued the studio for nonpayment before their contract was up. According to what Bob told Ken Griffis, ten dollars per song was all he and Tim received at best. About this time Tim’s older brother Glenn Spencer, a pianist and composer, began his association with the Pioneers and was to play an important role in directing their music and business activities. His songs were beautifully constructed and perfect for the Sons of the Pioneers.

“Tim and Bob were assigned songs to write for the movies and it was pretty much done in a 'let's get down to it' mode. But the other songs that they created - I can remember them stopping in the middle of dinners, parties or doing things together, and they would get an idea and go off and finish a song or start a song. They'd do that together a lot and they would do it separately, too.”

(Hal Spencer)“The studio gave Tim and I what they called a rough treatment of the story for the next picture. Tim and I would discuss the 'situation' in which the song is to be used. All this was dropped in the hopper and the grind began, guitars tuned and the framework of music and lyrics would take shape. Then the rest of the gang was called in and the songs tested for harmony possibilities and instrumentation. Out of these sessions come the finished product. Believe it or not, Tim and I once turned out four tunes in 24 hours. One time Columbia's Outpost of the Mounties was changed right in the middle of the shooting. We were asked to produce a tune as quickly as possible. We went to work and in two hours had a completely new and different original number. It was “Timber Trail” and Tim did the trick.”

(Bob Nolan, Tumbleweed Topics)

(Courtesy of an anonymous collector)

You can read more about the song folios here.

It was during these years that Bob found he had to distance himself slightly from the rest of the cast and crew to focus on his songwriting. As any writer knows, a lot of socializing is not conducive to creativity. Always a loner by inclination, Bob would now move out of earshot, in sight and available but away from the activity of the set or location. "You could tell from a lot of his songs that there was a guy who did a lot of tall thinking," considered Roy Rogers. Karl Farr Jr. recalls, "Bob was always off doing his own thing like one time on location in Kernville, California on a picture he took a tube and floated down the Kern River. He kept to himself a lot." Although the Pioneers understood, others did not and he slowly acquired the reputation of a recluse.

From Colorado Trail, 1938, singing "Bound for the Rio Grande"

(Karl E. Farr Collection)

Always the beach for relaxation. Here with Flash Whiting and friends.

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

Bob at the right.

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

"Just after the turn of the century a magazine was published titled "Physical Culture". It was all the rage with young men in the early part of the 20th Century and most were into body building and working out on the beach."

Gary Lynch, author of "Tom Blake Surfing 1922-1932" and historian for SURFER magazine in the late 80‘s.

The Sons of the Pioneers during the late 1930s were also guests on the popular Community Sing ten-minute short films, singing mostly public domain music. These shorts were directed by Sam Nelson and often included Donald Grayson singing off-screen. They were seen on screen only briefly as most of the film was karaoke-style lyric sheets for the audience to sing along with.

Community Sing, 1939

(Courtesy of Jan Scott collection)

Pat Brady remembered the 1938-39 period as being very busy, with the group appearing daily on radio station KHJ, which was located up over a Cadillac-LaSalle car agency at 7th and Bixel in Hollywood. While on KHJ, they appeared from 7-8 a. m. each day and on the Saturday Night Frolic, joined by the Stafford Sisters and several other acts. They participated in one of the early television test programs. They also began a new syndicated radio show, Sunshine Ranch. All the while, they were on the Columbia lot six days a week, filming. Lloyd married pretty Violet (Buddie) on September 6, 1938, in Las Vegas, Nevada.

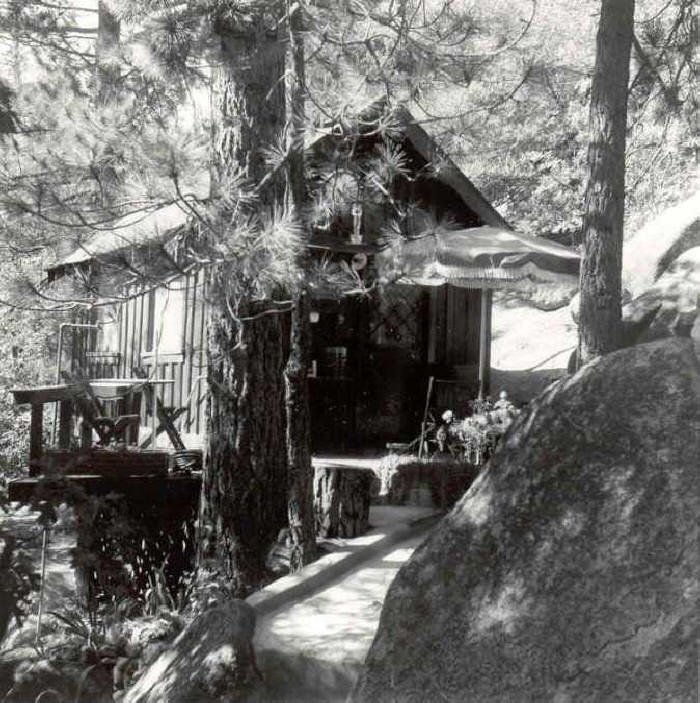

CABIN AT BIG BEAR LAKE

During the shooting of one of the Starrett movies on location at Big Bear Lake, Bob found and leased a little cabin that was to be his summer retreat for the rest of his life. "A lonely spot I know where no man will go where the shadows have all the room." ("Way Out There" by Bob Nolan)

“Well, it’s just a little shack that was built by a seventeen-year-old kid in 1925. This doggone little cabin, it has no frame at all, just boards straight up and down. But that wood is so hard and you’d swear and be damned---there’s so much weight on that roof---you’d just swear it would just buckle---the porch would go out from under it. But it don’t. It just stands there. And you can’t drive a nail in it. I have to take my electric drill and bore a hole in it just to drive a nail in it.

I talked to the man that built it and he built it in 1925 when he was seventeen. In 1925, how old was I? I was born in 1908. I thought we were just about the same age. I never asked him how old he was, but I figured he was about the same age as me. You see, his mother was the agent for the government that handed out the leases for the government up there and she had this one lot that she couldn’t get rid of. It was a son-of-a-gun to get to, see, so she gave it to her son if he’d build a cabin on it. She knew that if he could build a cabin on it, then she could sell it!

So he built this little cabin and it’s just right for me. It’s eighteen foot long, just about the length of this room and about twelve wide. Twelve by eighteen. And he set that doggone thing so that there’s four areas in it. It’s the perfectest laid out little place that you ever seen. There’s the kitchen area here and the sitting area here, the dining area here and the sleeping area. And there’s no walls between them, just an area. And I kept it just in the way he laid it out. Of course, I’ve done paneling and work and everything on it.

Now, from the outside it looks so rustic. You go to the inside and here I’ve got this beech wood paneling! I’ve got cubbyholes cut in the wall and cupolas on the outside where my electric ovens are. My ovens fit on the outside because I couldn’t find no room for it on the inside. I spend four months of every year there and I tried to stretch it into five months but I got caught in the snow a couple of times and got snowed in so I didn’t try it any more.”

Bob Nolan

Every Spring, as soon as the snow left the mountains and roads were passable, Bob would load up his Jeep or pickup and drive to Big Bear Lake. He lived simply for the next four months, cooked his own meals, and caught just one fish a day because one fish was all he could eat, he said. He continued his swimming in the cold lake. This is where he wrote many of his songs and where he regained the serenity he lost in the crowds he entertained. For the first few years, his wife P-Nuts accompanied him and worked in a little restaurant close by. But P-Nuts was a social person and eventually stayed behind in their home at Studio City.

“He was so very quiet and he didn't talk much at all but, after you knew him, you really liked Bob. He was very honest. But he was just so bashful all the time. We were like brothers.”

(Roy Rogers)

Sunshine Ranch

In 1939, the Pioneers began a new syndicated radio show, Sunshine Ranch, originally aired over KNX and the Mutual Broadcasting System and recorded by Allied Phonograph and Record Manufacturing Co. in Hollywood. "And now we turn for awhile from the busy highway of life, and down the winding lane that leads to Sunshine Ranch for a visit with our old friends Bob Nolan, Tim Spencer, Pat Brady, Lloyd Perryman and the Farr Brothers: Hugh and Karl. Here they are all set to bring us once again the songs and sentiments of the open range, songs in the distinctive style of the Sons of the Pioneers!" Karl took the part of an educated man in love with large words. Each man was Foreman for a Day, and there was a lot of good-natured banter and music. Unfortunately, most of the shows have been lost.

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

COMPLETE LIST OF THE MOVIES 1935–1940 THAT INCLUDED THE SONS OF THE PIONEERS

RADIO SCOUT (Warner Bros. / Brendel - 1935 05 06)

BRONCO BUSTER (Universal cartoon - 1935 08 05)

THE OLD HOMESTEAD (Liberty / Carlisle - 1935 08 10)

SLIGHTLY STATIC (MGM / Todd - 1935 09 07)

ROMANCE OF THE WEST (Warner Bros. short - 1935 11)

WAY UP THAR (Mack Sennett short - 1935 11 08)

GALLANT DEFENDER (Columbia / Starrett - 1935 11 30)

THE MYSTERIOUS AVENGER (Columbia / Starrett - 1936 02 01)

SONG OF THE SADDLE (Warner Bros / Foran - 1936 02 01)

RHYTHM ON THE RANGE (Paramount / Crosby - 1936 07 31)

THE CALIFORNIA MAIL (Warner Bros / Foran - 1936 11 14)

THE BIG SHOW (Republic / Autry - 1936 11 16)

THE OLD CORRAL (Republic / Autry - 1936 12 21)

THE OLD WYOMING TRAIL (Columbia / Starrett - 1937 11 08)

OUTLAWS OF THE PRAIRIE (Columbia / Starrett - 1937 12 31)

CATTLE RAIDERS (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 02 12)

COMMUNITY SING (Columbia - 1938 02 08)

CALL OF THE ROCKIES (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 04 30)

LAW OF THE PLAINS (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 05 12)

WEST OF CHEYENNE (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 06 30)

SOUTH OF ARIZONA (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 07 28)

THE COLORADO TRAIL (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 09 08)

WEST OF THE SANTA FE (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 10 03)

RIO GRANDE (Columbia / Starrett - 1938 12 08)

THE THUNDERING WEST (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 01 12)

TEXAS STAMPEDE (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 02 09)

NORTH OF THE YUKON (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 03 30)

SPOILERS OF THE RANGE (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 04 27)

WESTERN CARAVANS (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 06 15) .

THE MAN FROM SUNDOWN (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 07 15)

RIDERS OF BLACK RIVER (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 08 23)

OUTPOST OF THE MOUNTIES (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 09 14)

STRANGER FROM TEXAS (Columbia / Starrett - 1939 12 18)

TWO-FISTED RANGERS (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 01 04)

BULLETS FOR RUSTLERS (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 03 05)

BLAZING SIX SHOOTERS (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 04 04)

TEXAS STAGECOACH (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 05 23)

THE DURANGO KID (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 08 23)

WEST OF ABILENE (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 10 21)

THE THUNDERING FRONTIER (Columbia / Starrett - 1940 12 05)