Bob Nolan biography

1941–1942

“Pepper Rangers Gazette”, the fanzine from the Dr. Pepper Radio Shows.

Bob’s Life

Introduction - The Myth and the Man

1908 - 1931

1931 - 1935

1935 - 1940

1940 - 1941

1941 - 1942

1942 - 1943

1944 - 1946

1946 - 1949

1950 - 1980

Bob’s Family

Harry Nolan (father)

Flora Nobles Hayes (mother)

Earl Nolan (brother)

Mike Nolan (half-brother)

Mary Nolan Petty (half-sister)

Roberta Nolan Mileusnich (daughter)

Calin Coburn (grandson)

THE CAMEL CARAVAN

On their return from Chicago in the Fall of 1941, they signed with Camel Cigarettes' "Camel Caravan" and toured the west coast military bases.

"I remember the Phillips Oil Show had an audience. Pat was the comic but also Dad was fun. My dad did one number, "Cigarettes, Whiskey and Wild Wild Women" on stage with a worn out hat and two pie lids. I still have them."

(Karl E. Farr)

Yes, sir, we joined up with the west coast unit of the Camel Caravan and have been rollin' up and down the Pacific Coast from Port Townsend up in northern Washington, down thru the Redwood valleys of Oregon and California. This rig we've got is a dandy. First, we've got a bus as long as a movie kiss, a truck that's all rigged up into a collapsible stage. All we do is roll into the camp, drop down the sides of the truck and there's our stage. Just like an old time medicine show. Master of ceremonies is Herb Shriner. We are waiting for a call from Republic studios which we think will tell us to report about the 23rd for our first picture...with Roy Rogers. The plan is to fill our spot on the Camel Caravan temporarily with...Nora Lu and the Pals of the Golden West.

(by Hugh Farr, written in Tacoma, WA, Oct 17, 1941 1:00AM, p. 3, Tumbleweed Topics, Vol 1 No. 12 November 1941)

Tumbleweed Topics Vol 1 No 13, December, 1941

Tumbleweed Topics Vol 1 No 13, December, 1941

THE DR. PEPPER RADIO SHOWS (10-2-4 Ranch and 10-2-4 Time)

Left: 10-2-4 Ranch advertisement. Center: 10-2-4 Ranch transcription from the Dr. Pepper Museum. Right: Martha Mears

According to historian Ken Griffis, on November 22, 1941, the Pioneers signed to do a series of 15-minute radio transcriptions for the Dr. Pepper Bottling Company featuring Dick Foran (10-2-4 Ranch) and, later, Martha Mears (10-2-4 Time, broadcast from "the 10-2-4 Ranch"). This live show was broadcast from coast to coast on the Mutual Broadcasting System, and the Pioneers had a 45-minute stage show for the studio audience directly after it. The last Dr. Pepper program we have access to was August 30, 1945. (The earliest program we have access to was aired January 8, 1943.)

...around the 10th of November....started recording a series of 15 minute transcriptions for Dr. Pepper with Martha Mears and Dick Foran.

Hugh (Tumbleweed Topics Vol 1 No 13, December, 1941)

Although the group was announced as "Bob Nolan and the Sons of the Pioneers", we hear very little from Bob himself. Don Forbes, Martha Mears, Ken Carson and Hugh Farr had most of the dialogue. Martha and Ken sang at least one and often two solos.

List of songs from the 10-2-4 transcriptions.

Recalling these shows and the Teleways shows in later years to Doc Denning, Bob told him "Frankie Messina and Ivan Ditmars were fine musicians, and I love and respect them but I just wish the producers had let us do MY songs with just guitars and a fiddle. That's the way I wrote them, and that's the way they should be done."

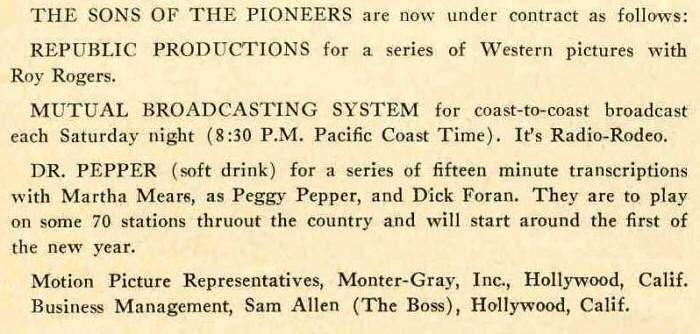

“In 1942, the Sons of the Pioneers were now under contract to Republic Pictures for a series of Western Pictures with Roy Rogers, Mutual Broadcasting System for coast-to-coast broadcast [Radio Rodeo] each Saturday night (8:30PM Pacific Coast Time), to Dr. Pepper (soft drink) for a series of fifteen-minute transcriptions with Martha Mears, as Peggy Pepper, and Dick Foran. The Dr. Pepper transcriptions were to play on some 70 stations throughout the country and start around the first part of 1942. The Pioneers' Motion Picture representatives, Monter-Gray, Hollywood, and their Business Manager (The Boss) Sam Allen, Hollywood.”

(p. 2 Tumbleweed Topics, No. 14 January 1942 Vol 2 No. 14)

The first Dr. Pepper show was possibly recorded on April 2, 1941, and aired on November 22, 1941. It ran until August of 1945. It cost $3,500 per week.

You can see more information and audio clips and a complete discography of the shows here.

There’s more information about the Pepper Ranger Gazette fanzine here.

(Photo courtesy of Laurence Zwhisohn)

RADIO RODEO

In December 1941 another contract was negotiated with Mutual for a series of Saturday night radio programs called Radio Rodeo. The programs were well received and the group reached an even wider listening audience. They also recorded for Decca between 1941 and 1942. These were extremely busy years because the Pioneers were also appearing at rodeos, benefits, bond sales activities, base hospitals, children's hospitals, and in programs like Hollywood Canteen where they performed free of charge as their patriotic duty.

“On Saturday, November 22 [1941], we began a coast-to-coast broadcast from Long Beach, California, to the Mutual Broadcasting System. It's released from WOR (in the east) at 11:30PM. It is our understanding that WGN (Chicago) transcribes the show and releases it the following Sunday morning. This is an audience show and we follow it with 45 minutes on the stage. The doors open at 7:30PM. Charley Lung (photo on p. 7), who portrays the part of Dad Cody, is known as the man of a thousand voices...he does a skit in which he takes 17 parts... try it sometime…. There's a possibility, motion picture commitments permitting, that we might take this Radio-Rodeo on tour and broadcast each Saturday night from wherever we happen to be.”

(Hugh Farr, p. 3 Tumbleweed Topics, Vol 1 No. 13, December 1941)

REPUBLIC PICTURES

The option of joining Roy Rogers had been considered by the Pioneers as early as July, 1940 (Tumbleweed Topics p. 2, Vol. 1, No. 9, July, 1940), but it wasn't until a year later that it came to pass.

"...I got some more news. The Sons of the Pioneers are being set for the first picture at Republic...with Roy Rogers. It will be a picture dealing with the Red River Valley country and present plans call for a closing number written by Tim and called “So Long to the Red River Valley”. By the way, we took a lot of pictures with Roy and Gabby Hayes on the Republic lot yesterday (September 29, 1941) .... Wait till you see the one of Pat pullin' the buggy and being led by Gabby.”

(Hugh Farr, p. 3, Tumbleweed Topics, October 1941 Vol 1 No. 11)“Thanks to Republic and our director, Joe Kane, the boys and I finally got to make a series of pictures together. The boys just got under the wire on the first one which was Red River Valley... it was already written before we knew they would be able to appear in it. As the magazine goes to press, we're shootin' the second one. Not titled yet.”

(Roy Rogers, p. 3 Tumbleweed Topics, Vol 1 No. 13, December 1941)“Got a call the 21st of October (we were up in Seattle) to check in at Republic on the 23rd. Had to give up the Camel Caravan, with which we were playing the army camps, and like the migratory birds we are, we flew south. Made Red River Valley with Roy...worked day and night and finished around the 10th of November... On the 21st of November we started our second picture with Roy. Don't know the title of it as yet. Bob and Tim wrote the songs (six of them) and Karl and yours truly wrote the instrumentals.”

(Hugh Farr, p. 3 Tumbleweed Topics, Vol 1 No. 13, December 1941)

Tumbleweed Topics Vol 1 No 11, October 1941

(John Fullerton Collection)

Back: Tim Spencer, Karl Farr. Front seat of buggy: Hugh Farr, Roy Rogers and Lloyd Perryman. Bob Nolan, holding back on the wheel, Pat Brady in harness with Gabby Hayes leading him.

September 29, 1941

(The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

Back with Roy for Red River Valley, September 29, 1941. Left: Courtesy of the Karl E. Farr collection. Right: The Calin Coburn Collection ©2004

September 29, 1941

The Sons of the Pioneers with Gabby Hayes, Herbert Yates and Sally Payne

In the Columbia pictures, Bob had a trademark light wool, tailored shirt and big white or black hat. He also had two immediately recognizable outfits in the Republic films: 1. A "working cowboy" garb usually included a dark brown leather open vest and 2: for dress: a black shirt with white piping plus a white silk scarf à la Charles Starrett with a pair of dark pants with a narrow stripe, . The Pioneers were responsible for purchasing their own costumes for all the films and, according to Karl E. Farr, bought them from Nudie's Rodeo Tailors.

The move to Republic, although it forever linked "Bob Nolan and the Sons of the Pioneers" with Roy Rogers in the minds of that generation, meant a steady diminution of Bob's roles. His role as second lead was gradually replaced by comedians, George "Gabby" Hayes, Smiley Burnette, Andy Devine, and Pat Brady. Several films became more like "song and dance" Broadway imitations that sometimes required Bob and the Pioneers to appear with the dance chorus. Tim Spencer's and Jack Elliott's songs were increasingly selected over his own. Tim's songs were catchy tunes—light and cheery—and Jack Elliott's bore the stamp of the studio composer. Bob's did not. He remained true to his own strict standards and fewer and fewer of his songs were used. He did write one or two light songs during this period but he felt they were phony and he was never happy with them. Still, each one was carefully crafted even if it was a novelty song. In a nutshell, his roles in the Roy Rogers movies were frivolous in comparison to the second lead action parts he'd had with Charles Starrett, and his serious songs were ignored. The up side was the international exposure generated by his ties with the Roy Rogers movies.

Bells of Rosarita (1945) gave him his largest role in a Roy Rogers film. He had a lot of amusing dialogue as an actor who played a cowboy singer who didn't like horses. His part called for a showy back flip, part of a choreographed dance scene with Adele Mara. A 1942 role in Sunset Serenade was good, particularly at the end where he was responsible for setting off a cherry bomb in Gabby Hayes' pie. That scene should have been redone because Bob was laughing instead of miming his part in the song while his recorded voice sang on. But, because it was spontaneous and very funny, it was left in. He had a decent role in Sunset on the Desert but in the remainder of the Roy Rogers' films, he was given group or semi-comedic parts as opposed to the serious roles he had in the Columbia Starrett movies. A seed of disillusionment began to take root.

Still, disappointment and disgruntlement was all in the future. Now, in 1942, his first year with Republic, "tomorrow" looked bright and challenging. Both on and off-screen the Pioneers were reaching new heights of popularity.

In the January 1942 issue of Tumbleweed Topics, Hugh Farr gave us the following insight into the making of the Roy Rogers films.

“When Tumbleweed Topics last went to press, we were in the middle of the second picture with Roy at Republic. Since then we have finished that picture and one additional – that makes three down the pipe since your combination fiddler-tattler picked up the old goose-quill. Don't have the titles as yet. You know they assign some kind of 'working' title to the film when we start shooting and then later it picks up the title under which it is released.

Lots of folks have been asking for a story on just how they make these westerns. This is as good a time as any, so here we go. First we get rough copies of the story with indications as to where the director wants the songs. Our song writing team (Bob and Tim) get busy and work up songs to fit the situation. There's always the opening song, which is usually a riding tempo as we nearly always ride into the picture. Then another one fitted in someplace to give the audience a little rest from the action of the picture. That's the one they usually cut all to pieces by fading it down and going right ahead with the villain crawling through the bushes with the knife in his mouth, anyway. Then there's usually a campfire song, you know, slow and sweet. Then perhaps a comedy song and the closer. Then Karl and I work out the instrumental interludes or what have you.

When they get ready to start the picture, the first thing is the recording of the songs and music. This is recorded and when the actual shooting of the picture starts they bring it out in a can together with a play-back machine. As the action, to which the music is fitted, commences, they play this music or these songs back and we play and sing in tempo with the music we hear, so that they wind up with the music and the action in sync.

The strictly action shots – that is, the chases and outdoor scenes – are usually the first made. Later comes the inside shots – the interiors. The average western picture runs about 57 minutes and is made up of about 1200 separate scenes. Many of the westerns are made in eight days! "Eight Day Epics" they call them. If you don't think that's stepping just consider that means about 150 scenes per day (8 hours). Republic takes longer, but Republic makes better westerns than the average.

Many of the scenes are taken more than once, some of them as much as a dozen times. Somebody reads a line with the wrong emphasis on the right part or the right emphasis on the wrong part or some mistake is made in wardrobe.

The scenes are not made in the order in which they appear in the completed film as this would require too much setting up and breaking down of sets. When they once get a scene set up, they try to make all the scenes in which that set is used right then and there, even though in the story several days may be supposed to pass between the two scenes.

The finished film usually runs about 5000 feet. They actually take about 20,000 feet. It's up to the director to select the shots of a particular scene that he likes best. When this selection has been made, the cutter takes charge of the film and he trims it down to the actual negative of the film that is sent to your theatre. Of course, there's the editing and a thousand and one other operations but I'm saving them for the day when I get too old to ride and shoot and holler and fiddle. Then maybe I'll start a correspondence course in how to make moving pictures – that is, if I learn how myself.”

(Hugh Farr)

Bob added to the picture:

“For food, they sent catering companies out to wherever we were. Say we were working out of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, or just out of Las Vegas up here, why they make all those arrangements before we go out on the location. The new location might be ten miles away from town and they send the trucks out there at a certain time and they allow us only half an hour to eat. What I’m trying to get across here is location work is not as nice and free as sitting around the set where you’re enclosed and you can only go so far and you just sit there and you read or knit. But on a location, time is so valuable that the picture is now costing ten times as much in time than it is if you’re on your own bluff over here, and every minute is just like thousands of dollars going down the drain, see?

And you have to work. And tempers and temperaments are at their highest pitch and I could never see any reason to have anything musical happen out there. The director, the assistant director, the cameraman, everybody is just gritting their teeth all of the time because of the horrible cost of money to take a company out on location. And you’ve got to remember, we were making "B" pictures, see, and when you get out out on location, the price was same as if you were an "A". We tried to keep production time to nine days. A whole picture in nine days! That gives you a little picture of the pressure. We could only shoot until the sun went down. Then we went home and slept—believe me, we did! They just took you back to the motel and put you to bed.

I had one fall and that was my own fault because I shouldn’t have attempted to do the thing that they wanted me to do [in South of Santa Fe]. The stunt was to rope Gabby Hayes’ Tin Lizzie which was stuck in a mud hole, see. I take my dallies around and pull him out with my horse. My horse, when he turned to go away, stepped over that rope and that’s all she wrote, you know. He broke in two and I went up and down and right under his feet. Now, this horse is tethered to this rope and he can’t get away from it and it’s all over. But he never touched me once. And I could feel the air of his feet, his hooves, going past me. One of those, if it had caught me right in the head, I was through. That’s all. But that put the end of me trying to do any kind of a stunt. I called for a stuntman every time.

(Bob Nolan - Cox Larimer Interview April 28, 1976)

Bob now understood that an accident could put an end to his career. Acting was only a small part of how he made his living. It may have taken up a lot of his time, but it put very few dollars into his bank account. He was a professional singer - not only in the movies but on radio, on recordings, in personal appearances and shows over the whole country. An injury to Bob would have had a detrimental effect to the salaries of the rest of the Sons of the Pioneers. He was the front man, the best-known member of the group and his voice was the basis of the Sons of the Pioneers' inimitable sound. Rex Allen agreed in a similar situation that his own voice was more important than risking losing it by doing the stunts himself:

“I got hit in the Adam’s apple one time. A guy named Bob Cason (a.k.a. John) had me down and was hitting me towards the head. I was laying on my back and evidently didn’t move right or he made a mistake and he hit me in the Adam’s apple. We had to close down the picture for three days because I couldn’t talk. It very well could have been a permanent thing.”

Yakima Canutt, stuntman and second unit director par excellence, put it this way:

“Many of the stars are capable and willing to do their own stunts, but with a tight schedule and thousands of dollars tied up in a picture, it's too much of a gamble. Should a star break a leg, an arm, or even get his face skinned a little, the overhead goes up while the actor recuperates. Should a stunt man get injured, he can be replaced without any loss of time. A stunt man is always a good insurance policy for any action picture.”

Bob had no special riding skills when he started in the movies although he could ride a little. Most people could ride a little in the early 1930s. But to gallop headlong over rugged country again and again in countless chase scenes required more than average skill if both horse and rider were to escape injury. Riding in the close formation required to keep all the Pioneers and Roy in the camera lens was dangerous in itself. So, he hired a stuntman to teach him. Thereafter, Bob was easily recognizable in the "posse" when it was galloping after the villains. The lessons from the stuntman taught him to ride with his elbows out and hands together in front of him. None of the other Pioneers or Roy rode like that but a keen eye will find others who did in the chase scenes. Bob became a capable horseman, learning various skills such as the ‘flying dismount’.

Bob’s instantly recognizable riding form.

Bob’s flying dismount in the movie Utah

Although most of the dangerous stunts were performed by stuntmen, Bob was still required to learn some basic fighting and defence techniques for his roles in film.

While Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers look on, Armed Forces judo instructor Cliff Freeland, gives Bob instruction on how to block and disarm a man with a knife. You can see from the instructor's face, that Bob is putting a fair amount of pressure on his arm.

“He was a mighty man. He was stout. He was a man's man, old Bob. He'd take a drink with you or fight or whatever you wanted to do, but he was a genius as far as the stuff he wrote and the way he presented it.”

(Richard Farnsworth, actor and stuntman.)

(Courtesy of the Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

(Courtesy of a private collector)

(Courtesy of the Terry Sevigny collection)

(Courtesy of the Terry Sevigny collection)

WRITING THE MUSIC FOR THE MOVIES

“I've often thought, "What a God-given talent it takes to write such a beautiful song as "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" about a thing so ugly and useless as a tumbleweed."“

(Patsy Montana)

Bob wrote his verses on whatever was handy wherever he happened to be – on a napkin in a bar or restaurant or in a tiny black book he kept in his shirt pocket. In the July 1940 issue of Tumbleweed Topics, Bob goes into the song-making side of the movies a little more thoroughly and the photos following are scanned pages from one of his little notebooks.

“The studio gives Tim and I what they called a rough treatment of the story for the next picture. Tim and I get together and discuss the situation in which the song is to be used. All this is dropped in the hopper and the grind begins, guitars are tuned, and the framework of music and lyric takes shape. Then the rest of the gang are called in and the songs are tested for harmony possibilities and the instrumentation. Out of these sessions come the finished product. Believe it or not, Tim and I have turned out four tunes in twenty-four hours! One time not long ago, Columbia's picture, Outpost of the Mounties, was changed right in the middle of the shooting. We were asked to produce a tune as quickly as possible. We went to work and in two hours had a completely new and original number. It was "The Timber Trail" and Tim did the trick.”

(Bob Nolan)

A little black coil-bound notebook that Bob kept in his pocket. (It was smaller than these images.)

(Courtesy of The Calin Coburn Collections ©2004)

In a later interview, Bob enlarged on Tim and Bob's songwriting:

"Tim and I divided the work up and went off and worked separately. In other words, if we had eight songs, it’d be, "I’ll take this one, I’ll take this one," see? That’s the way we divided them." (Bob Nolan - Cox Larimer Interview April 28, 1976)

When asked if working under the pressure of getting them out was an aid in writing the songs, Bob replied,

"Well, it was an aid to getting them out on time! Whether we were doing good work or not, I don’t know. I happen to know that 'Timber Trail' is a beautiful song that Tim wrote but he come up with that in an awful big hurry. I don’t like to write under pressure but I did it because of the double standard they had on us---because we had to do it. It was in our contract. Tim and I were the only songwriters of the group, so we had to do it all."

(Bob Nolan - Cox Larimer Interview April 28, 1976)

Ken Griffis in Hear My Song quotes Bob as saying that he and Tim worked better alone and wrote very few songs together:

"Unless I did the major portion of the song, such as Blue Prairie, I wouldn't put my name on it. Over the years I did help Timmy on several tunes."

(p. 32, Hear My Song by Ken Griffis, 1994)

Bob loved poetry and read and kept a great deal of it. A careful scrutiny of his lyrics does reveal the influence of his favorite British Romantic Poets and Edgar Allan Poe. To read more about this, go to Poetic Influences.

“He had no library. He had his book of philosophers open by his chair most of the time. I can no longer recall what it was, specifically. He read a great deal of poetry.”

(Roberta Nolan Mileusnich)

Cy Feuer was the musical director for more than 125 Republic movies. He describes the process of making the music in this short interview from The Music of Republic: The Early Years 1937-1941 (CindeDisc CDC 1018):

For more on Bob Nolan’s songwriting, see Bob Nolan, Songwriter.

COMPLETE LIST OF THE MOVIES 1941–1942 THAT INCLUDED THE SONS OF THE PIONEERS

THE PINTO KID (Columbia / Starrett - 1941 02 05)

OUTLAWS OF THE PANHANDLE (Columbia / Starrett - 1941 02 27)

RED RIVER VALLEY (Republic / Rogers - 1941 12 12)

MAN FROM CHEYENNE (Republic / Rogers - 1942 01 16)

SOUTH OF SANTA FE (Republic / Rogers - 1942 02 17)

SUNSET ON THE DESERT (Republic / Rogers - 1942 04 01)

ROMANCE ON THE RANGE (Republic / Rogers - 1942 05 18)

SONS OF THE PIONEERS (Republic / Rogers - 1942 07 02)

CALL OF THE CANYON (Republic / Autry - 1942 08 10)

SUNSET SERENADE (Republic / Rogers - 1942 09 14)

HEART OF THE GOLDEN WEST (Republic / Rogers - 1942 12 11)

RIDIN’ DOWN THE CANYON (Republic / Rogers - 1942 12 30)